ANTIBIOTIC STEWARDSHIP

Antibiotics have transformed the practice of medicine, making once lethal infections readily treatable and making other medical advances, like cancer chemotherapy and organ transplants, possible. Prompt initiation of antibiotics to treat infections reduces morbidity and saves lives, for example, in cases of sepsis. However, about 30% of all antibiotics prescribed in acute care hospitals are either unnecessary or suboptimal.

Like all medications, antibiotics have serious adverse effects, which occur in roughly 20% of hospitalized patients who receive them. Patients who are unnecessarily exposed to antibiotics are placed at risk for these adverse events with no benefit. The misuse of antibiotics has also contributed to antibiotic resistance, a serious threat to public health.

Antibiotic resistance is rising to dangerously high levels in all parts of the world. New resistance mechanisms are emerging and spreading globally, threatening our ability to treat common infectious diseases. A growing list of infections – such as pneumonia, tuberculosis, blood poisoning, gonorrhea, and foodborne diseases – are becoming harder, and sometimes impossible to treat as antibiotics become less effective.

Where antibiotics can be bought for human or animal use without a prescription, the emergence and spread of resistance are made worse. Similarly, in countries without standard treatment guidelines, antibiotics are often over-prescribed by health workers and veterinarians and overused by the public. The only way to keep antimicrobial agents useful is to use them appropriately and judiciously, this is where “Antibiotics stewardship” comes in.

Antibiotic stewardship

Antibiotic stewardship is the effort to measure and improve how antibiotics are prescribed by clinicians and used by patients. Improving antibiotic prescribing and use is critical to effectively treat infections, protect patients from harm caused by unnecessary antibiotic use, and combat antibiotic resistance.

Antibiotic stewardship, sometimes also referred to as Antimicrobial Stewardship (AMS), is a joint effort by healthcare providers to embrace responsible prescribing of antibiotics. That includes prescribing antibiotics only when they are needed (i.e., for bacterial infections, not viral ones), prescribing the appropriate antibiotics for the diagnosed infection, and prescribing the right dose and duration of antibiotic treatment, among other things.

the aim of an AMS program is:

◦ To optimize the use of antibiotics

◦ To promote behavioral change in antibiotic prescribing and dispensing practices;

◦ To improve quality of care and patient outcomes;

◦ To save on unnecessary healthcare costs;

◦ To reduce further emergence, selection, and spread of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR);

◦ To prolong the lifespan of existing antibiotics;

◦ To limit the adverse economic impact of AMR; and

◦ To build the best-practices capacity of healthcare professionals regarding the rational use of antibiotics.

TYPES OF ANTIBIOTICS STEWARDSHIP INTERVENTION

In The Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs, the CDC laid out three main types of stewardship interventions that can improve the use of antibiotics: broad interventions, pharmacy-driven interventions, and specific interventions for infections and syndromes.

1) Broad interventions involve getting prior authorization to prescribe certain antibiotics, performing audits on cases involving antibiotics, and re-evaluating the antibiotics prescribed while diagnostic information is being collected. For example, you’re given ciprofloxacin in the emergency room for a suspected kidney infection while your blood work is sent to the lab; once your results come back, the prescribing physician revisits your info to see if that’s still the best antibiotic for you.

2) Pharmacy-driven interventions include adjusting doses of antibiotics, looking out for duplicate therapies and drug interactions, and assisting with transitions from IV to oral antibiotics.

3) Infection/syndrome-specific interventions offer clear instructions for prescribers on using antibiotics to treat many infections with a history of antibiotic overuse, including community-acquired pneumonia, urinary tract infections, skin and soft tissue infections, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections (MRSA), Clostridium difficile infections (C. diff), and bloodstream infections that have been proven by culture.

Award recipients achieve measurable and meaningful progress in providing care that is:

- Safe

- Timely

- Effective

- Efficient

- Equitable

- Patient-centred

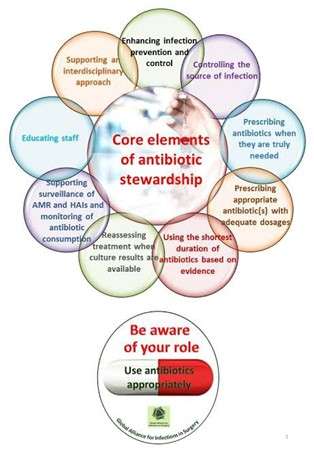

THE CORE ELEMENTS FOR SUCCESSFUL IMPLEMENTATION OF ANTIBIOTICS STEWARDSHIP IN HOSPITALS.

According to CDC, Core Elements of Antibiotic Stewardship offer providers and facilities a set of key principles to guide efforts to improve antibiotic use and, therefore, advance patient safety and improve outcomes.

The CDC recognizes that there is no “one size fits all” approach to optimize antibiotic use for all settings. The complexity of medical decision-making surrounding antibiotic use and the variability in facility size.

Optimizing the use of antibiotics is critical to effectively treat infections, protect patients from harm caused by unnecessary antibiotic use, and combat antibiotic resistance. Antibiotic stewardship programs can help clinicians improve clinical outcomes and minimize harm by improving antibiotic prescribing.

In 2019, CDC updated the hospital Core Elements to reflect both lessons learned from five years of experience as well as new evidence from the field of antibiotic stewardship. Major updates to the hospital’s Core Elements include:

1) Hospital Leadership Commitment: This involves the necessary human, financial, and information technology resources. Support from the senior leadership of the hospital, especially the chief medical officer, chief nursing officer, and director of pharmacy, is critical to the success of antibiotic stewardship programs. Also, giving stewardship program leader(s) time to manage the program and conduct daily stewardship interventions.

Providing resources, including staffing, to operate the program effectively. Having regular meetings with leaders of the stewardship program to assess the resources needed to accomplish the hospital’s goals for improving antibiotic use.

2) Accountability: This program must have a leader or co-leaders, such as a physician and pharmacist, responsible for program management and outcomes. Effective leadership, management, and communication skills are essential for the leaders of a hospital antibiotic stewardship program.

3) Pharmacy Expertise: This core element was previously known as Drug Expertise; it was renamed to reflect the importance of pharmacy engagement for leading implementation efforts to improve antibiotic use and so it is important to identify a pharmacist who is empowered to lead implementation efforts to improve antibiotic use. Infectious diseases-trained pharmacists are highly effective in improving antibiotic use and often help lead programs in larger hospitals and healthcare systems.

4) Action: Antibiotic stewardship interventions improve patient outcomes. An initial assessment of antibiotic prescribing can help identify potential targets for interventions.

Stewardship programs should choose interventions that will best address gaps in antibiotic prescribing and consider prioritizing prospective audit and feedback, preauthorization, and facility-specific treatment guidelines. Though, prospective audit and feedback (sometimes called post-prescription review) and preauthorization are the two most effective antibiotic stewardship interventions in hospitals.

Prospective audit and feedback are an external review of antibiotic therapy by an expert in antibiotic use, accompanied by suggestions to optimize use, at some point after the agent has been prescribed, while Pre-Authorization requires prescribers to gain approval prior to the use of certain antibiotics. This can help optimize initial empiric therapy because it allows for expert input on antibiotic selection and dosing, which can be lifesaving in serious infections, like sepsis. It can also prevent unnecessary initiation of antibiotics.

Facility-specific treatment guidelines are also considered a priority because they can greatly enhance the effectiveness of both prospective audit and feedback and preauthorization by establishing clear recommendations for optimal antibiotic use at the hospital. These guidelines can optimize antibiotic selection and duration, particularly for common indications for antibiotic use like community-acquired pneumonia, urinary tract infection, intra-abdominal infection, skin and soft tissue infection, and surgical prophylaxis.

5) Tracking: Measurement is critical to identify opportunities for improvement and assess the impact of interventions. Measurement of antibiotic stewardship interventions may involve evaluation of both processes and outcomes. For example, a program will need to evaluate if policies and guidelines are being followed as expected (processes) and if interventions have improved patient outcomes and antibiotic use (outcomes).

6) Reporting: Antibiotic stewardship programs should provide regular updates to prescribers, pharmacists, and nurses on process and outcome measures that address both national and local issues, including antibiotic resistance. Antibiotic resistance information should be prepared in collaboration with the hospital’s microbiology lab and infection control and healthcare epidemiology department. Information on antibiotic use and resistance along with antibiotic stewardship program work should be shared regularly with hospital leadership and the hospital board.

7) Education: This is a key component of comprehensive efforts to improve hospital antibiotic use; however, education alone is not an effective stewardship intervention. Education is most effective when paired with interventions and measurement of outcomes. Case-based education can be especially powerful, so prospective audits with feedback and preauthorization are both good methods to provide education on antibiotic use.

Patient education is also an important focus for antibiotic stewardship programs. It is important for patients to know what antibiotics they are receiving and for what reason(s). They should also be educated about adverse effects and signs and symptoms that they should share with providers.

Nurses are an especially important partner for patient education efforts. They should be engaged in developing educational materials and educating patients about appropriate antibiotic use.

Antibiotic stewardship programs in the Intensive Care Unit: why? How? And where are they leading

Antimicrobial stewardship programs are typically hospital-based programs designed to ensure that patients receive the right antibiotic, at the right dose, at the right time, and for the right duration. Antibiotic stewardship programs (ASP) are regarded as a keystone in tackling Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) in Intensive Care Units (ICU). The aim is to reduce antibiotic resistance by minimizing selection pressure, and by optimizing antibiotic therapy.

The intensive care unit (ICU) is often regarded as an epicenter of infections, added to the fact that it represents the heaviest antibiotic burden within hospitals; with sepsis being the second non-cardiac cause of mortality. Some major studies in Europe show that 50% of all patients had infections from the ICU. Further studies have shown that mortality from Sepsis in the critically ill can approach 50%, with time to initiation of antibiotic treatment as the single strongest predictor of outcome.

These mortality rates are increased by 7% with each hour’s delay, over the first 6h. ICUs account for 5%-15% of total hospital beds but 10%-25% of total healthcare costs. Sepsis increases patient-related costs six-fold. Empiric practice, which might be deemed necessary at the point of care, due to uncertainty of causative organisms, is often ineffective and results in higher costs, and an increase in resistant organisms. All these pose major challenges to patient management.

Within the ICU setting itself, causes of AMR may conveniently be categorized by procedure-related, management-related, and antibiotic-related factors.

Procedure-related factors include central venous catheters and endotracheal intubation for mechanical ventilation. Management-related factors include poor adherence to infection control policy, lack of microbiological surveillance with delayed/failed recognition of resistant isolates, patient overcrowding, understaffing and implicit spread of AMR through human vectors, prolonged ICU length of stay, and pre-infection with resistant organisms at the time of ICU admission. Antibiotic-related factors are related to the appropriateness and duration of treatment. Although only shown in hospital wards rather than ICU, failure to de-escalate or discontinue therapy is also a likely contributory factor to antibiotic resistance in ICU.

THE SUPPLEMENTAL ANTIBIOTICS STEWARDSHIP STRATEGIES.

1) De-escalation of therapy: Include conversion from empirical combination therapy to targeted monotherapy based on knowledge of the isolated microorganism, susceptibility, and infectious disease. It should be initiated early on (after 48–72 h), which also includes discontinuation of initial therapy if the diagnosis is not secured. De-escalation programs should point out that depending on the exact diagnosis in some cases instead of de-escalation, escalation may in fact be necessary.

2)Guideline and Clinical Pathways: The Antibiotic Stewardship (ABS) team should utilize local guidelines and anti-infective point-of-care chart reviews to draw attention to the excessive duration of treatment frequently encountered in practice. The ABS team should define the duration of treatment recommended as a rule, since this is expected to impact substantially on anti-infective drug use, side effects, and costs.

3)Parenteral-to-oral conversion therapy: If sufficient bioavailability is assured, and if the patient’s condition allows, therapy should be switched from parenteral to oral antibiotic application. This measure reduces the length of hospital stay and the risk of line-related adverse events. This implementation ought to be facilitated by developing clinical criteria and through explicit designation in institutional guidelines or clinical pathways.

4) Dose optimization: Adequate adjustment and optimization of the dose and dosing interval are essential for effective, safe, and responsible administration of anti-infective therapy, and an important part of ABS programs. Besides individual patient factors, optimal dosing of anti-infective should take into account the nature and severity of illness, the causative microorganism, concomitant medications, as well as the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the agents prescribed. Strategies to optimize dosing in ABS programs should include an assessment of organ function for drug dose adjustment in order to avoid adverse drug events and unwanted drug interactions.

5) Scheduled switch/ cycling of antimicrobials: Strategic rotation of specific antimicrobial drugs or antimicrobial drug classes ought to be undertaken to limit the selective pressures and to achieve a reduction of infectious microorganisms or microorganisms displaying specific resistance properties for a certain time.

There is evidence to suggest that a balanced use of different antimicrobial drugs or antimicrobial drug classes, can minimize the emergence of resistance. In both cases, routine surveillance of antimicrobial drug use and resistance should be performed.

Guiding Principles for Prescribing Antibiotics

- Determine the likelihood of a bacterial infection. Signs and symptoms of bacterial URIs can be similar to those of viral infections. Physicians must take care to ensure the patient has a bacterial infection before prescribing antibiotics.

- Weigh the benefits against the harms of antibiotics. If a physician determines the infection is bacterial, he or she should make sure the pros of the antibiotic, such as cure rate and symptom reduction, outweigh the cons, such as antibiotic-related infection and cost.

- Implement judicious prescribing strategies. These include selecting the proper antibiotic, determining the proper dosage, and identifying the shortest possible treatment time.

Conclusion

Antibiotic stewardship practices, principles, and interventions are critical steps toward containing and mitigating antimicrobial resistance. They are designed to promote, improve, monitor, and evaluate the rational use of antimicrobials to preserve their future effectiveness, along with the promotion and protection of public health. ASP has proven highly successful in promoting the rational use of antimicrobials through the implementation of evidence-based interventions. Its principles and core elements are embedded in the WHO Global Action Plan on AMR and should be factored into national strategies against AMR. The holistic and multisectoral “One Health” initiative is also needed to address AMR. The WHO recognizes this global threat and strongly recommends implementing this approach at the national and global levels.

Reference

- A/RES/71/3, Political declaration of the high-level meeting of the General Assembly on antimicrobial resistance, New York: United Nations; 2016,

- Arnold HM, Micek ST, Skrupky LP, Kollef MH. Antibiotic stewardship in the intensive care unit. Semin Respir Crit Care Med.

- Davey P, Brown E, Charani E, Fenelon L, Gould IM, Ramsay CRet al

Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices for hospital

Inpatients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2013 Apr 30;4: CD003543. Update in Davey P, Marwick CA, Scott CL, Charani E, McNeil K, Brown E et al. Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices for hospital

Inpatients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2017 Feb 9;2:CD003543.

- Deege MP, Paterson DL. Reducing the development of antibiotic resistance in critical care units. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2011;12:2062–2069.

- Global framework for development and stewardship to combat antimicrobial

resistance: draft roadmap. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017,

- Jenkins TC, Stella SA, Cervantes L, Knepper BC, Sabel AL, Price CS, Shockley L, Hanley ME, Mehler PS, Burman WJ. Targets for antibiotic and healthcare resource stewardship in inpatient community-acquired pneumonia: a comparison of management practices with National Guideline Recommendations. Infection. 2013;41:135–144

- Resolution WHA 68-7. Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance. In: Sixty-eighth World Health Assembly, Geneva, 26 May 2015. Annex 3, Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

- Schuts E, Hulscher ME, Mouton JW, Verduin CM, Stuart JWTC, Overdiek HWPM et al. Current evidence on hospital antimicrobial stewardship objectives; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis, 2016;16:847-56.

- Stemming the superbug tide: just a few dollars more. Paris: OECD; 201 B,

- McGowan JE, Gerding DN. Does antibiotic restriction prevent resistance? New Horiz.1996,4:370-6.

- Towards better stewardship: concepts and critical issues, Geneva: World

Health Organization; 2002.

- WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, 20th List. Geneva: World Health

Organization; 2017:8-15.